After conducting this interview, the whole world changed in just a matter of a few weeks – or even days. We entered a state of isolation, where people are closing their doors from physical contact and the comfort of the rituals of our everyday life. Our perception of the passage of time is changing – it’s extending, stretching in new ways, and we are looking for new ways to fill it. This is a theme that also interests artists Maija Tammi and Niina Vatanen, both of whom have treated time in their works. Time is an inseparable part of our bodies, our memories, experiences and our very existence.

15.03.2020

I sit down at the institute’s café with Maija Tammi and Niina Vatanen. The two artists have spent a few days in springlike Paris and participated in the opening of Festival Circulation(s) on the preceding evening, where their work is exhibited. The Circulation(s) festival is held at the infamous 104 CENTQUATRE, a cultural centre in northern Paris. The annual festival celebrates contemporary European photography and works as a stepping stone for young photographers.

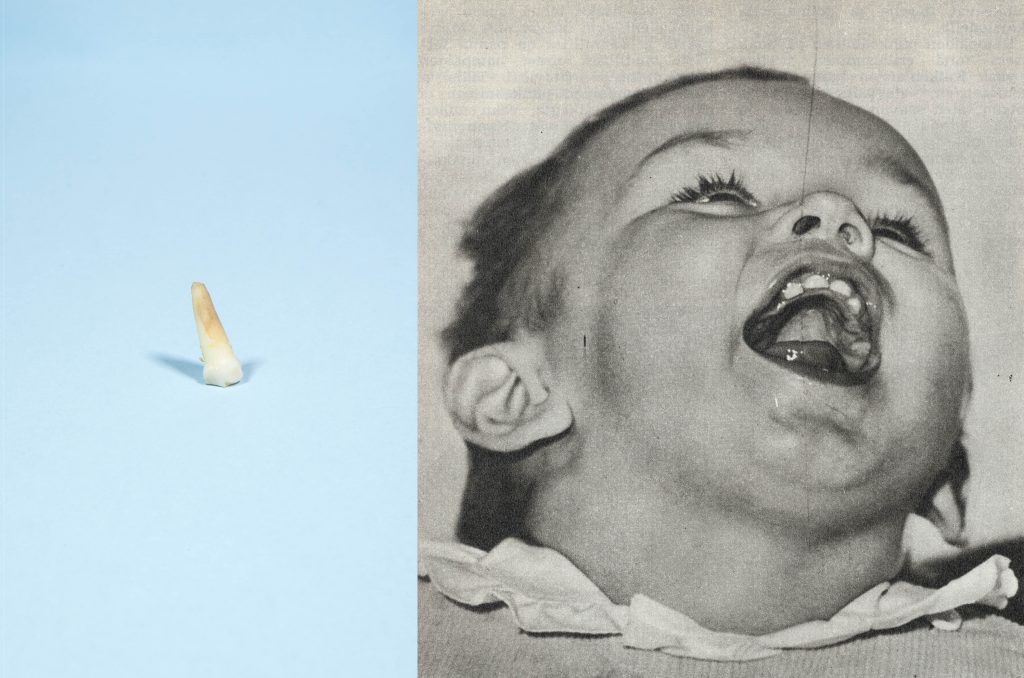

Niina Vatanen’s exhibition at the festival is based on her latest book, Time Atlas. As the book’s title suggests, Time Atlas deals with the notion of time. Vatanen creates layers to her images through painting, cutting, glueing and re-photographing. The photographs deliver from archives, Internet, old encyclopedias, manuals and textbooks, which she weaves together by following her intuition and themes. The overlapping photographs create a tapestry of time in which history, memories and experiences become an inseparable part of time and our perception of it. Time travels through photographs, it creates trails through forests, smooths out the edges of rocks, creates shadows and falls trees.

For Maija Tammi, time is also a fascination. On view at Festival Circulation(s) is Tammi’s work, White Rabbit Fever. The exhibition deals with time and its relation to death and immortality as well as examines the borders between beauty and disgust. Through the exhibition, the photographer explores when a living being ceases to exist. In her video work, we can witness a dead rabbit fading away and becoming a part of a forest. We also see photographs of carcinogenic cells that belong to Henrietta Lacks, a woman who died of cancer decades ago. The cells keep on living in laboratories all around the world. For Tammi, time becomes visible through life and death. Death is what gives meaning to our experience of time.

“When you start to study time, it often goes back to religion and science, but the subjective experience of time is something much more complicated. “

I asked the two photographers about their shared interest in time.

Niina: I discovered this theme when working with an archive project at the Finnish Museum of Photography more than 5 years ago. I was going through an archive of 5000 negatives of an amateur photographer. Time has always been present in my works, but with this particular project, when scanning through an archive of perished negatives, the passage of time turned into something rather touchable. When you start to study time, it often goes back to religion and science, but the subjective experience of time is something much more complicated.

Maija: As for me, time is much more linked to human’s corporality, immortality and mortality. I am interested in how mortality, or the physical aspect of it, is bound to time and especially to how we perceive time. It has been proved in some research that is not age, but how much time people think they have left, that will determine what they want to do with their time and what they consider to be important.

Niina: Time is such an abstract subject, that I have tried to approach it playfully. I don’t think “playful” is the right word, as it is often associated with something naive, or even insignificant. With this project, I did my best to preserve a light and fun approach on time as a counterbalance for this theme, often too vast and recurrent.

Maija: As for me, I’ve tried to focus on concrete things, such as the infinite growth of carcinogenic cells or the mouldering of a rabbit; when a living being ceases to exist and starts to be something else. It is often thought that the boundary between life and death is explicit. However, a human being can be dead in different ways: clinically, biologically, and, when speaking of organ donation, some bodies are kept alive artificially, with the help of machinery.

Niina: Time is also a very built-in part of a camera – the shutter speed, the fact that you can save a glimpse of time. It is one of the key elements of photography.

Maija: By the way, the rabbit in my work exhibited at Circulation(s) is from a high-end Parisian restaurant. I bought two dead rabbits from there because I didn’t know where I would have been able to find them otherwise. I was doing a residence in Hôtel le Chevillon, from where I took a train to Paris and picked up a box of dead rabbits.

Niina started her studies in the early 2000s at the School of Arts, Design and Architecture, where she had her M.A. in 2008. As for Maija, she has a doctorate in arts and has worked as a photojournalist before beginning her artistic career. Even if photography has played a big part in both of their lives for a long time, their relationship with photography does not come without contradictions.

Maija: I work with photography the most but for me, it is simply one medium among others. I don’t identify only as a photographer, but rather as an artist.

Niina: I first started to develop an interest in photography through working in the darkroom, because it’s quite a magical process. I started my studies in photography at the School of Art and Design in 2000. At that time, the education was completely analogue. Photography is a native language to me, the fundamentals of work, but my work is continuously expanding to other artistic fields. At the same time, my relationship with photography is quite contradictory. I use a lot of found elements in my photographs but I don’t take that many pictures myself. The photograph itself is of interest to me and I think my education in analogue photography highly influences what I think of photography. At the moment it does not matter to me what tool I use in order to create photos – I can equally shoot on film, on digital, on my smartphone or scan. And I create new pictures from old ones. I have always loved to look at photo albums when visiting grandparents for example. I really enjoy looking at photographs of strangers.

Maija: Bravo, hats off to you!

Niina: What, you don’t like it? I love it!

Niina: What was interesting about this archive project was the fact that 5 000 negatives formed 40 years of this person’s life. Nowadays, a person can take as many photos during a two-week vacation.

Maija: Of course I also want to document my life in some way, more so now that I have a child, but for that, I have only used Polaroids. I use my phone more to take notes than to take photos. If I have a camera in my hand, I’m going to photograph in earnest! For me, it is not possible to take photos unseriously.

Niina: I often take pictures with my phone, and I actually shoot more because of it. Cameras are way too heavy and you can’t carry them everywhere with you. A smartphone has become a very good tool for me and I am rather proud of it, especially when you take my background into account! After graduation, I had to learn new ways to work because photography had changed a lot and the darkroom equipment I had used to work with, were not used anymore. Being able to take pictures with my phone has truly been liberating.

“We put things into value according to the amount of time that was spent on them. This is also a constraint of photography because people think it is so quick and easy. When in reality that’s what makes photography so much harder.”

Maija: Everything you’ve said, is, in a way, linked to time. We are used to thinking that if something takes a lot of time, then it is inevitably better. You could be crafting a table for ten years, and it could still be a bad table. Sometimes it’s like, we put things into value according to the amount of time that was spent on them. This is also a constraint of photography because people think it is so quick and easy. When in reality that’s what makes photography so much harder.

Maija: I had an exhibition called One Picture Manifesto with three other artists in the Finnish Museum of Photography. The exhibition wants to highlight the significance of a single photograph and stand against the serialism of photography – one photograph should be enough. The process turned out to be extremely difficult for us three because you had to be able to say everything in just one photo. I shot the same photo about 800 times to get that one almost perfect picture.

Usually, I either start working from a very large theme and kinda narrow it down during the process, or, as I did with One Picture Manifesto, the concept needs to be ready before I can start shooting.

Niina: When working with my book I did the opposite – although of course all the nearly 280 pictures are in it for a reason. And had to delete a lot of them.

Maija: My next exhibition is called Immortals birthday. I am still interested in the theme of immortality, but this time, instead of carcinogenic cells, the exhibition will focus on the hydra, a one-centimetre long fresh-water polyp, which does not age at all. A hydra can clone itself – for example if you cut a hydra into 8 pieces, from each one will grow a new hydra. It’s a superstar of regeneration. A very strange and tiny animal. The exhibition will also include some greek mythology and take a look at immortality from different perspectives.

Niina: I will continue with the theme of time. I would love for this theme to become a lifetime project. I won’t be making a new book right away, but the book format is very appealing to me in its democracy. Exhibitions will last for a certain amount of time and only a few people will be able to see it. A book lasts time and is easy to distribute around the world. I think that books are permanent places for my works. Around them, exhibitions have a life of their own and there my works have an organic, constantly changing form.

Just like the rest of Paris, Festival Circulation(s) had, unfortunately, to close its doors due to the propagation of Covid-19. The festival, however, continues to bring young European photography alive through daily artistic telegrams from participating photographers. You can follow the online project, STAY HOME(S), on their website or on their Instagram.

Text: Veera Mietola