Juhani Pallasmaa is a Finnish architect and the former professor of architecture at the Helsinki University of Technology. He is also the former Director of the Museum of Finnish Architecture. His most notable architectural works include Kamppi Centre in Helsinki, Rovaniemi Art Museum and the Finnish Institute in France. Juhani Pallasmaa has written and published over 60 books and 400 essays, and he is the honorary member of the Finnish Association of Architects and the American Institute of Architects, and an honorary doctorate of five universities.

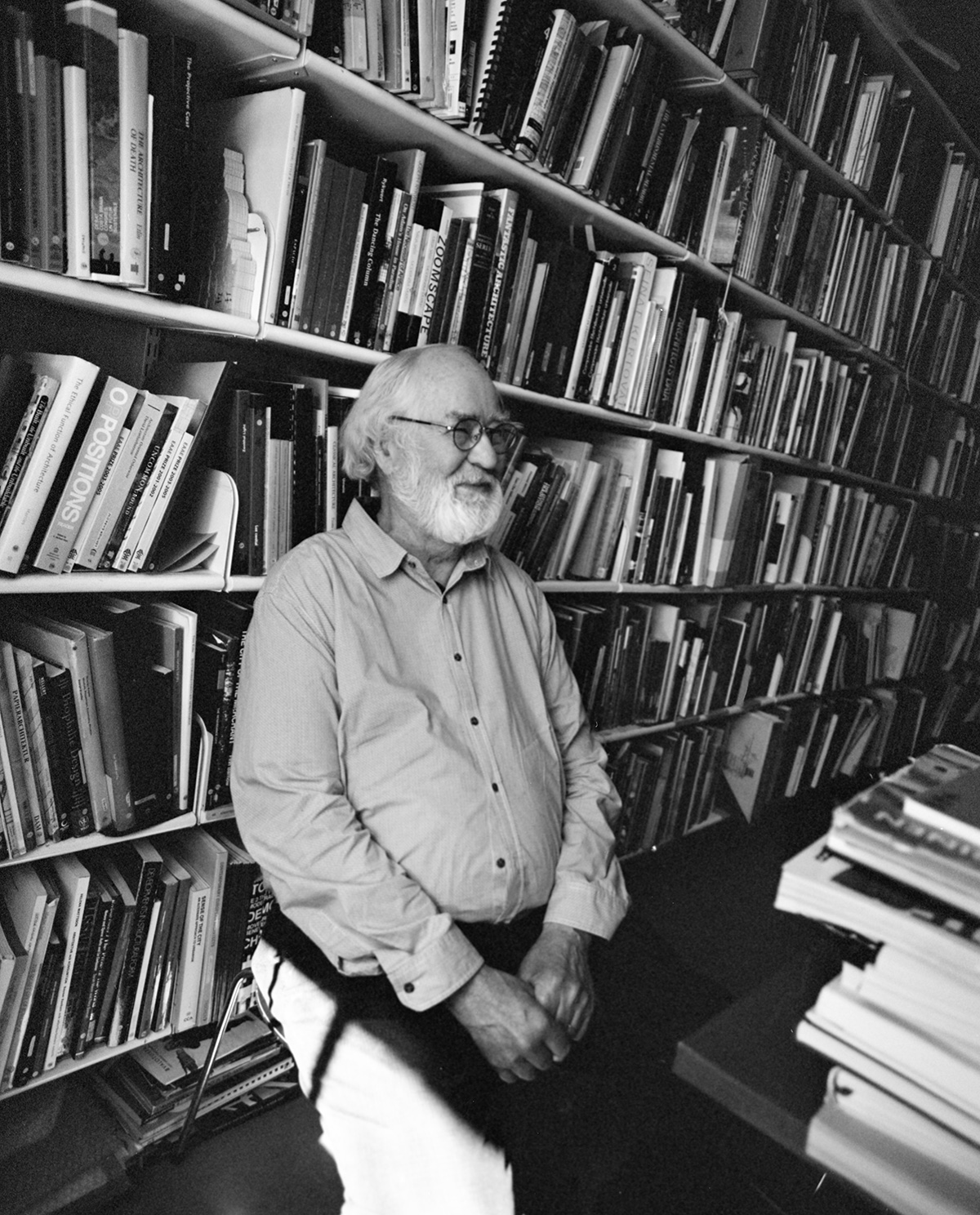

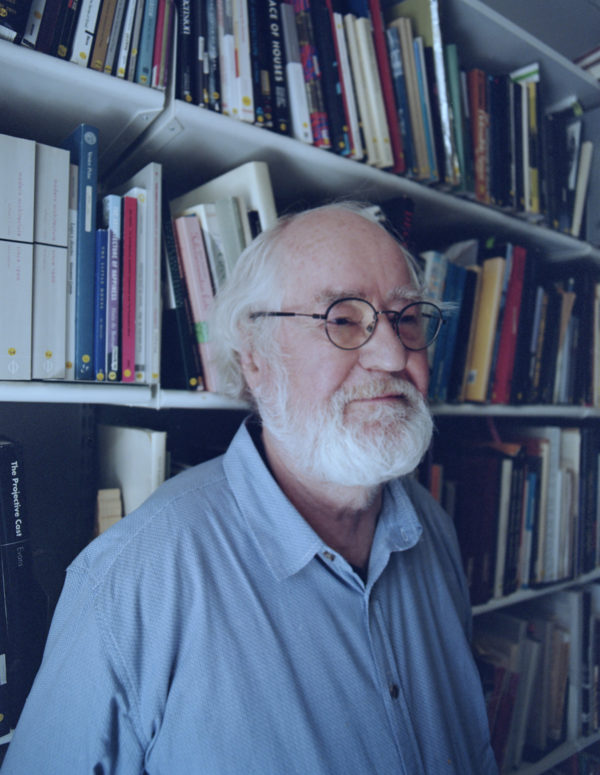

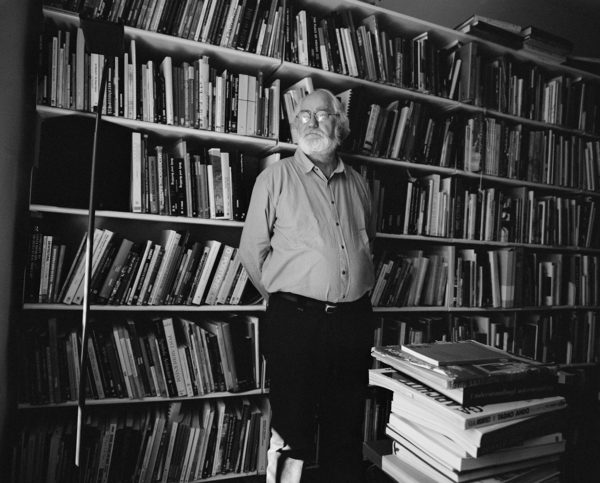

One morning in early May I had a meeting with Juhani Pallasmaa in his office on Tehtaankatu, in Helsinki. Upon entering his study, which was bathing in spring light and covered with bookshelves, I immediately sensed an intriguing combination of warmth, lightness and grace. I had no pre-arranged plan, nor carefully detailed questions prior to our meeting; I was curious to see where the conversation would lead. A wide range of topics was discussed during the encounter: the horizon of Helsinki and fishing in the lake Inari, ideas of touch and patience. Numerous citations, thoughts about literature and arts. Above all, stories about life.

You are well-known for a widely multidisciplinary practice and never-ending curiosity, you teach, have worked in architecture and urban planning, and also in exhibition, product and graphic design. How did you end up in the field of architecture?

I was born in Hämeenlinna and grew up in Helsinki. During the wartime, I spent a lot of time in my grandfather’s country house. This developed into a significant period in my life, and I tend to go back to those memories more and more often. My grandfather was a farmer, and I used to observe him in his daily tasks: I learned so much from him. Above all, I spent enormous amount of time alone in nature, just observing nature and its animals.

I am not quite sure how I ended up in architecture. When I was still a schoolboy, I used to dream of studying medicine. I was supposed to become a surgeon and spent my school years reading biographies of world-famous surgeons. On the day when I was supposed to register at the university, I ended up walking in the department of architecture. When I saw the amazing perspective drawings by Eliel Saarinen of his Munkkiniemi-Haaga plan, I knew that my profession was chosen.

When I grew up in the countryside, I got very used to the idea that everybody shares the same tasks. This is when I started thinking that human beings are able to do everything. I have put this into practice by not respecting the established boundaries between different fields. Last fall in Paris I held a lecture about infinity in a conference on mathematics. Before I was asked to participate, I had not given any thought to the topic. My childhood experiences can be found in the background of all this: I easily get excited about new things. Some people see this as excessive ambition, but it is not about that. I would define it as a simple curiosity of a farm kid.

When entering a new space, be it a room or a city, it only takes a fraction of a second for an overall sensation to form. I have written a lot about how the atmospheric sense is our sixth sense, maybe the most important one of all of our senses.

Writing and literature have always played an essential role in your life. You have written and edited more than 60 books and 400 essays, which have been published in many languages. How do you see the process of writing?

Even though I have never written fiction per se, the literary tone has become more important in my writings throughout the time. My style is very associative. When writing, I do not normally write any outlines, I just write directly. This is how the text develops into what it wants, or the situation requires. Milan Kundera, who writes about the wisdom of novel, has noted how a good novel is always wiser than its writer. If the writer feels wiser than its text, then one should change career. I can say the same thing about my writings.

I always have the same process when writing: I do everything over and over again and repeat it always ten times. The very first version is always handwritten. During the first five rounds, I feel like it is my writing, and the five other times I am just looking what the text suggests itself, and give space for its development.

You often talk about the importance of different senses together with the notion of holistic experience. How would you distinguish understanding which is based purely on knowledge on one hand, and on immediate observation and experience on the other hand?

Nature and all its animals are perfectly wise. So are human beings deep down. This is closely linked with the notion of survival in different conditions.

When we talk about knowledge or knowledge-related understanding, I distinguish three different levels: information, knowledge and wisdom. In my opinion, the first two levels should not be taught anymore at schools and universities, but rather, they should belong to the inherited tradition and cultural background. Unfortunately, this does not exist any longer. The role of the universities should be to synthesise all these diverse fundamental elements into wisdom. When teaching in universities, I notice that many students do not possess the basis that should be normally provided by home and culture, and we have to go through basic concepts quite often.

Wisdom is not related to knowledge, it is interwoven with the idea of selfhood, and with the comprehension of the bigger picture. Wisdom flourishes through life experience: it is a product of life. Of course one can study it, and the best way to learn it is through literature, which is condensed life. The most endangered field of our times is the comprehension and mastery of entities: everything gets fragmented, and these fragments are available easier and faster than ever before. However, they do not create an entity if no framework can be found around them.

In one of your seminal works, « The Eyes of the Skin » which first came out in 1996, you talk about the sight dominance when observing one’s surroundings. Even though it has been over twenty years since the book first came out, the topic seems more current than ever. How do you see the role of technology in architecture?

I see technology as a sort of extension of human beings. All the technology extends our bodily or intellectual characteristics and abilities. This means that technology is not something that is external, but rather, an integral part of us. It is dangerous to trust in technology and mechanics blindly: it always changes its user and it is not innocent. Computers, for instance, have a direct impact on the nervous system.

I am worried about running after all the things imaginable, without giving any thought to the possible consequences. A good example of this is how they stopped teaching cursive handwriting in Finnish schools. Cursive handwriting incarnates writing and the text and is also closely linked to the understanding of the reading process. This describes the schooling system’s incapacity to understand the idea of the unity of human beings, the continuity of body and mind. Just yesterday I read the well-known passage from Dostoevsky’s Idiot, where prince Mushkin gives examples of cursive writing for his future employer: he writes the same sentence in six different styles, and all of them are described with a few words. This reflects how many different meanings are hidden in handwriting.

The idea of fragmentation that you mentioned previously sums up pretty well our postmodern era and evokes questions about the notions of time and space. How do you approach these themes in the context of teaching?

Italo Calvino writes about how time was an essential concept in the 19th-century literature, and in the 20th-century space has turned into the essential concept. Normally people do not tend to connect time-related experience or content to architecture, but I think these are equally important notions. Architecture enables living both in time and space.

French architect-philosopher Paul Virilio writes how the pace is the most crucial product in today’s society. I am thankful for the years of boredom that I experienced in my childhood. Children should get bored in order to stimulate their inner creativeness. Besides the notion of patience, I often talk to my students about insecurity. Nowadays the only thing that is pursued in schools is confidence. Surely it is something to aim to, but one should be able to tolerate insecurity next to it.

You regularly bring up the importance of your childhood environment, life in the countryside and nature, which have followed you throughout your path. What is the imagery of your mindscape?

It can be found in a Finnish forest. When travelling around the world and sleeping in hotels, the last thing I see before falling asleep is an image of the surface of a lake, observed from the forest, through tree trunks. Forest is an important place for me, and I have written a lot about it. If I am anxious for some reason, everything settles down by going to the forest for a half an hour.

You have mentioned in one of your interviews that you used to see modernism through the invention of new, but now you consider it more through dialogue. What is the importance of the history of architecture and all its layers in your work?

My relationship to time, history and technology has radically changed from what it used to be. I was part of the generation of futurologists, who in the 1960’s strongly believed in the realm of mind, the possibilities offered by technology and the triumph of democracy. All these areas have disappointed me.

I did not care so much about history when I was younger. Instead of history as a science, I consider more important the understanding of history. T.S. Eliot formulated well in his essay « Tradition and the Individual Talent » from 1919 the notion of “the historical sense”. This refers to the history of life and history of culture. For me, the importance of this has grown throughout the years. Through this notion, I understand myself both as a designer and writer, being a layer in the continuity of time. This is also the reason why I use so many quotes all the time: I wish to express the tradition of this and that, instead of proposing something as my own invention.

There is a lot of conversation going on in Finland about the growing inequalities and their impact on urban planning, especially in the light of today’s booming construction trend. What are your thoughts about this?

The growing inequalities can be observed in all the fields. It makes sad to think how the concept of the northern welfare system has disappeared. There are many absurdities in our times: the never-ending privatization, measuring everything through money and all sorts of extremisms worry me.

What are the first things you pay attention to when entering in a new environment? What is the importance of details for you?

When entering a new space, whether it is a room or a city, I get an all-encompassing sensation in a fraction of a second. I have written a lot about how the atmospheric sense is our sixth sense, maybe the most important one of all our senses. Even though this was discussed to some extent in the German aesthetics of the end of the 19th century, it has only recently been more discussed in the architectural world.

The mastery of details is an important skill. The details cannot be too active, otherwise, the consistency of the atmosphere shatters. For example, details serve the touch which is related to our eyesight. We touch with our eyes. Often, the more historical architecture and design offer pleasant touch experiences for eyes, whereas the more recent architecture is quite often sharp and angular: pleasant surfaces, textures and shapes are absent. I consider this idea of the sense of touch hidden in sight very important. Every time when I design an object or building, I touch it in my mind instead of looking. I can feel the lines on my skin.

When I was younger, I was not so interested in materials. My attitude has changed also with regards to this. Gaston Bachelard divides mental images into two different categories; imagery of shape and material. The images of material are deeper and the material is the subconsciousness of the shape. This is a beautiful expression. Bachelard has also pointed out how science can not say anything about a lived life: only art delivers sensations about life, and in this, I agree.

Photos: Emma Sarpaniemi

Texte: Sini Rinne-Kanto